The Fourth Leaf

Closer Look to Reading Small Changes and Luck

If it’s luck, then I’m hacking the universe, Warsaw, 2016

White clover grows almost everywhere in temperate regions — in lawns, along roadsides, in fields, and between paving stones. It is so common that it rarely invites attention. Yet from this ordinary plant comes one of the most persistent symbols of luck: the four-leaf clover. Clover typically produces three leaflets, and when a fourth appears, it interrupts a pattern so familiar that it immediately stands out. For centuries, that interruption has been interpreted as good fortune, largely because it occurs infrequently enough to feel exceptional.

But rarity is not fixed. It arises from biological processes operating under particular environmental conditions, and if those conditions shift, the frequency of variation may shift as well. The cultural meaning of the four-leaf clover has remained stable, but the environments in which clover grows have changed dramatically.

The Structure Behind the Form

White clover (Trifolium repens) is characteristically trifoliate. Three leaflets form through a tightly regulated developmental process controlled by interacting genetic pathways during early growth. The species is an allotetraploid (2n = 4x = 32), carrying four chromosome sets derived from two ancestral species — a form of polyploidy that often provides developmental flexibility, since duplicate gene copies can buffer harmful mutations while also allowing variation in how traits are expressed.

Leaflet number is determined early in development, when growth tissues establish how many leaflet primordia will form. Under typical conditions, that system reliably produces three. A fourth leaflet appears when regulatory processes shift, whether through recessive genetic expression, somatic mutation, or altered gene expression influenced by environmental factors. The four-leaf form is therefore not a separate species or a botanical anomaly in the dramatic sense, but a variation within a stable and adaptable developmental system.

Rarity and Context

The commonly cited figure of one four-leaf clover in every 10,000 plants is cultural rather than strictly empirical. Observed frequencies vary widely across regions and environments: in some locations, the ratio may approach one in several thousand; in others, it is much lower.

More informative than any single number is the distribution. Four-leaf clovers often appear clustered within particular patches, which suggests that local conditions — genetic or environmental — influence developmental outcomes. This does not establish direct causation; genetic variation alone can produce additional leaflets. However, plant development is sensitive to context, and clustering indicates that context deserves attention.

Developmental Stability and Environmental Stress

Plant development depends on regulatory precision. Environmental stress — including drought, nutrient imbalance, heavy metals, herbicides, atmospheric pollutants, or radiation — can alter hormonal signalling and gene expression during critical growth stages. When these regulatory systems are disrupted, developmental stability decreases: an increase in morphological variation that biologists refer to as developmental instability.

Research in radiation-affected regions illustrates this clearly. Studies conducted in the Chernobyl exclusion zone documented elevated mutation rates and increased developmental abnormalities in plants and animals exposed to chronic radiation. As Anders Pape Møller and Timothy Mousseau noted in their long-term assessments, sustained environmental stress produced measurable biological effects across multiple species. Radiation represents an extreme case — most landscapes are not comparable to nuclear exclusion zones — but the underlying biological mechanisms operate across many forms of environmental stress. Disruption of DNA repair pathways, oxidative stress, and altered gene regulation differ in intensity from one stressor to the next, not in principle.

None of this means that every four-leaf clover signals contamination. Natural morphological variation occurs independently of human disturbance. But it does mean that environmental conditions can influence how genetic potential is expressed.

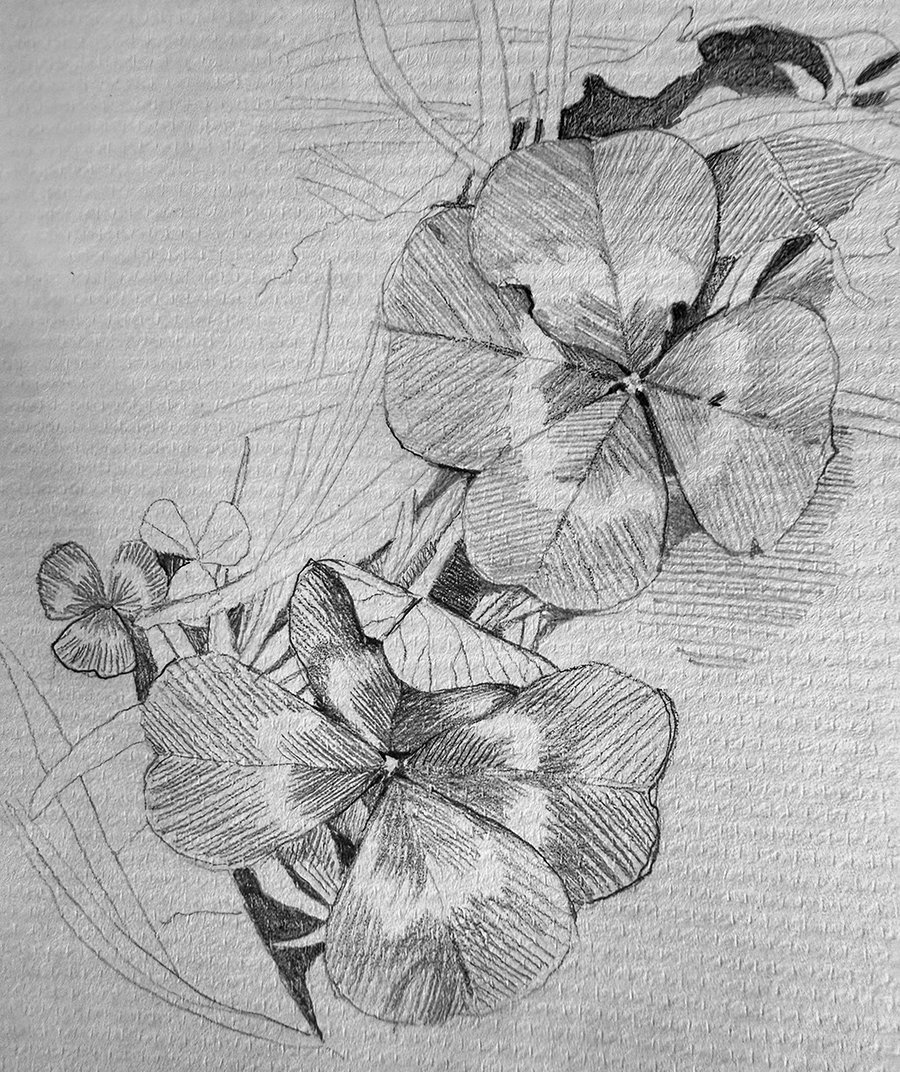

Clovers (from notes) — Mira Maria Belniak, Kanie, 2017

Clover as an Ecological Model

White clover has already demonstrated sensitivity to environmental gradients. Its cyanogenesis polymorphism — whether a plant produces hydrogen cyanide as a defence compound — varies predictably between urban and rural environments. Research has shown that urban heat islands and winter temperature patterns influence the distribution of cyanogenic and acyanogenic forms. These findings establish an important precedent: visible traits in clover populations can reflect environmental context.

Leaflet number has not been studied as extensively as cyanogenesis, but it belongs to the same conceptual framework. If one visible trait tracks environmental conditions, it is reasonable to consider whether others may also respond to local stressors. Ecologists define bioindicators as organisms whose biological responses provide information about environmental quality — lichens for air pollution, aquatic invertebrates for water quality. White clover is not formally classified as a leaflet-number bioindicator, but its wide distribution and visible variability make it an accessible organism for observation. When morphological variation appears concentrated in specific environments, investigation is warranted — not as proof of damage, but as an inquiry into possible influence.

Epigenetic Context

Environmental effects on plants extend beyond immediate physiological responses. Epigenetic modifications — changes in gene expression that do not alter the DNA sequence — can be triggered by stress, and some may persist across generations. Research in plant molecular biology has shown that stress-induced epigenetic changes can influence adaptation and genomic stability. Whether leaflet number itself is shaped by such mechanisms remains under investigation, but the broader principle is established: plant form can reflect environmental history as well as present conditions. Variation may therefore carry traces of accumulated context.

Reconsidering the Symbol

The four-leaf clover entered cultural imagination when variation was unexplained and relatively rare, and its scarcity supported its interpretation as a sign of luck. Scientific understanding does not eliminate that meaning — it adds dimension. If environmental conditions influence developmental stability, then the four-leaf form represents both genetic variation and environmental interaction.

This dual perspective does not require alarmism. An additional leaflet is a small deviation. It does not signal ecological collapse. But it reflects the responsiveness of living systems to surrounding conditions, and that responsiveness is worth noticing.

Attention and Responsibility

Environmental change today is often incremental. Nitrogen deposition increases gradually, trace pollutants accumulate slowly, and temperature averages shift over decades. These processes rarely produce immediate spectacle; they alter probabilities. Plants frequently register such changes early — through altered flowering times, shifts in species distribution, and increased morphological variability.

An extra leaflet is subtle. It is not definitive evidence of environmental stress, but one expression of developmental flexibility within a living system responding to its context. Finding a four-leaf clover can remain a simple pleasure. It can also prompt a broader awareness that variation has causes, and that living organisms respond continuously to the environments they inhabit.

The symbol endures because it captures attention. Biology adds context to that attention. The extra leaflet may represent chance, but it also reflects the sensitivity of life to its surroundings. The question is not whether a four-leaf clover is lucky. The more useful question is what conditions made it possible — and what those conditions tell us about the landscapes we share with it.

References / Further Reading

1. Genetics and Polyploidy of Trifolium repens:

- Ellison, N. W., Liston, A., Steiner, J. J., Williams, W. M., & Taylor, N. L. (2006). Molecular phylogenetics of the clover genus (Trifolium—Leguminosae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 39(3), 688–705.

- Hand, M. L., Ponting, R. C., Drayton, M. C., Lawless, M. T., Cogan, N. O. I., Sawbridge, T. I., … Spangenberg, G. C. (2008). Identification of homologous genomic regions within Trifolium repens and related species. BMC Genomics, 9, 607.

- Wendel, J. F. (2000). Genome evolution in polyploids. Plant Molecular Biology, 42, 225–249.

- Soltis, P. S., & Soltis, D. E. (2016). Ancient WGD events as drivers of key innovations in angiosperms. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 30, 159–165.

2. Developmental Instability and Morphological Variation:

- Graham, J. H., Raz, S., Hel-Or, H., & Nevo, E. (2010). Fluctuating asymmetry: Methods, theory, and applications. Symmetry, 2(2), 466–540.

- Møller, A. P., & Swaddle, J. P. (1997). Asymmetry, Developmental Stability, and Evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Debat, V., & David, P. (2001). Mapping phenotypes: Canalisation, plasticity, and developmental stability. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16(10), 555–561.

3. Environmental Stress and Mutation / Genomic Instability:

- Britt, A. B. (1996). DNA damage and repair in plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology, 47, 75–100.

- Gill, S. S., & Tuteja, N. (2010). Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 48(12), 909–930.

- Kovalchuk, I., & Kovalchuk, O. (2012). Epigenetics in health and disease. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis, 53(5), 363–374.

- Boyko, A., & Kovalchuk, I. (2011). Genetic and epigenetic effects of plant–pathogen interactions. Molecular Plant, 4(6), 1014–1023.

4. Chernobyl and Radiation Ecology:

- Møller, A. P., & Mousseau, T. A. (2006). Biological consequences of Chernobyl: 20 years on. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 21(4), 200–207.

- Møller, A. P., & Mousseau, T. A. (2015). Strong effects of ionising radiation from Chernobyl on mutation rates. Scientific Reports, 5, 8363.

- UNSCEAR (United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation). (2008). Sources and Effects of Ionising Radiation: UNSCEAR 2008 Report.

5. Epigenetics and Stress Memory in Plants:

- Boyko, A., Blevins, T., Yao, Y., Golubov, A., Bilichak, A., Ilnytskyy, Y., … Kovalchuk, I. (2010). Transgenerational adaptation of Arabidopsis to stress requires DNA methylation and the function of Dicer-like proteins. PLoS ONE, 5(3), e9514.

- Lämke, J., & Bäurle, I. (2017). Epigenetic and chromatin-based mechanisms in environmental stress adaptation and stress memory in plants. Genome Biology, 18, 124.

6. Clover Cyanogenesis and Urban Evolution:

- Thompson, K. A., Renaudin, M., & Johnson, M. T. J. (2016). Urbanisation drives the evolution of parallel clines in plant populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 283(1845), 20162180.

- Johnson, M. T. J., Thompson, K. A., & Saini, H. S. (2015). Plant evolution in the urban jungle. American Journal of Botany, 102(12), 1951–1953.

- Santangelo, J. S., Rivkin, L. R., & Johnson, M. T. J. (2018). The evolution of city life. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 285(1884), 20181529.

7. Bioindicators and Ecological Monitoring:

- Markert, B., Breure, A. M., & Zechmeister, H. G. (2003). Bioindicators and Biomonitors: Principles, Concepts and Applications. Elsevier.

- Parmar, T. K., Rawtani, D., & Agrawal, Y. K. (2016). Bioindicators: The natural indicator of environmental pollution. Frontiers in Life Science, 9(2), 110–118.

8. Cultural History of the Four-Leaf Clover:

- Hutton, R. (1996). The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford University Press.

- Briggs, K. (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies. Pantheon Books.

- Simpson, J., & Roud, S. (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford University Press.