X:BRFM

The ecological reality of multi-leaf clovers

The X stands for the unknown: in this case, the unpredictable outcome of a drawing made without conscious intent.

I began this series with no plan, no sketch, no image in mind. Using a marker pen on small sheets of paper, I made each drawing whilst deliberately avoiding focus on what I was making. The goal was to bypass rational thought — to let the hand move without the mind directing it. André Breton called this “the dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason.” Psychic automatism. I wanted to see what would emerge.

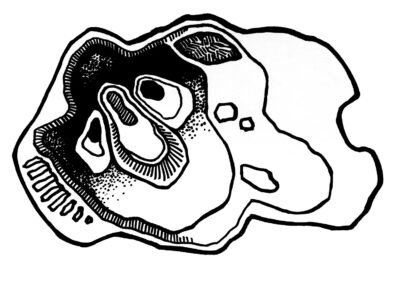

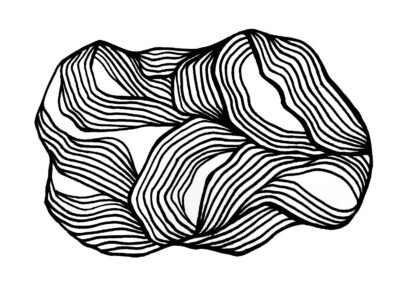

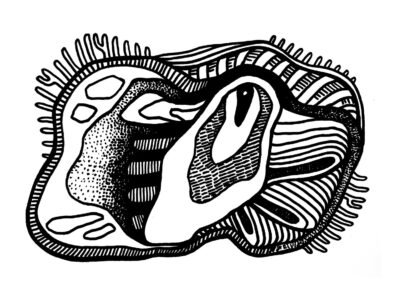

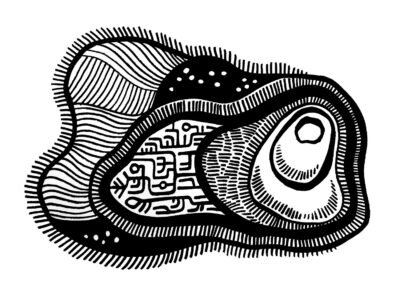

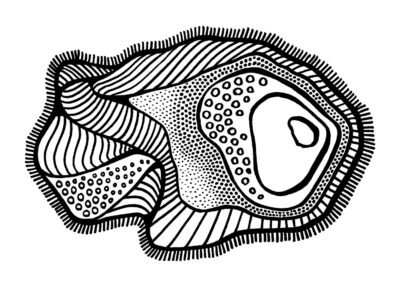

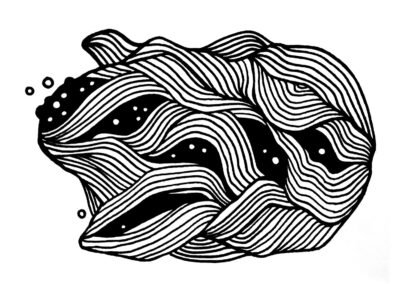

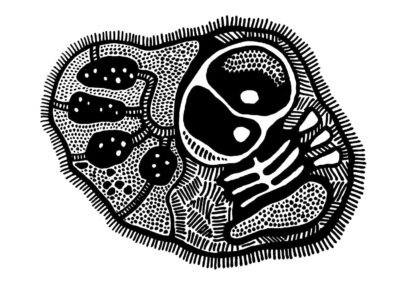

What emerged was biological.

The process

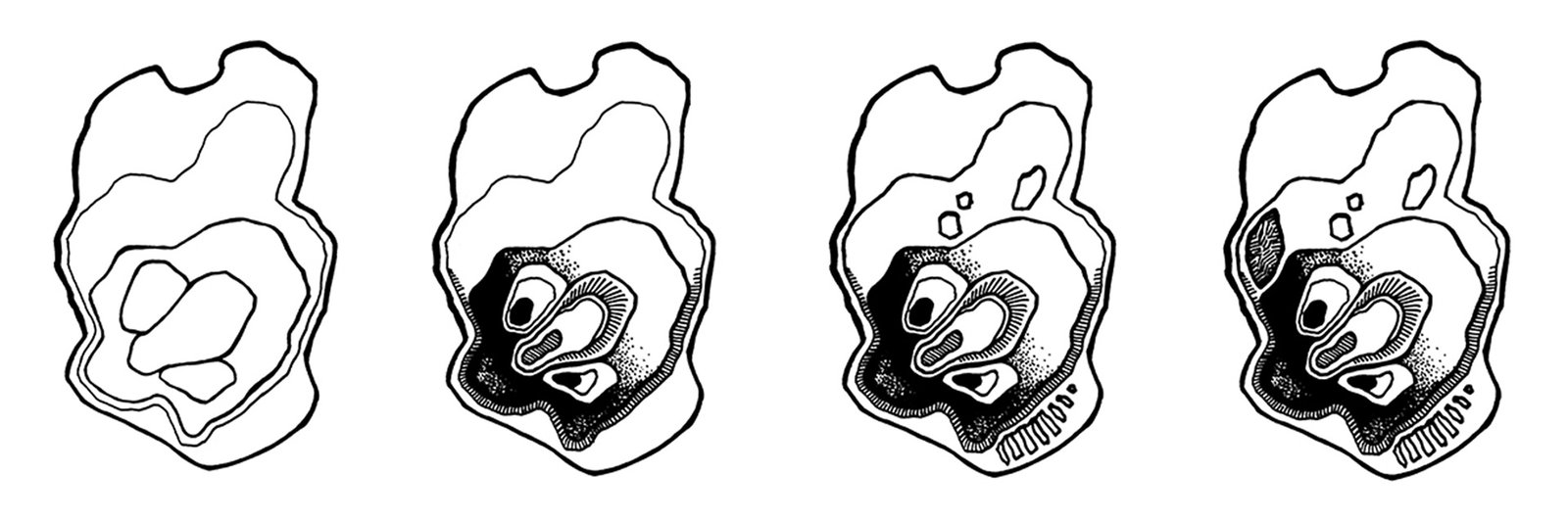

Automatic drawing has a long history. The Surrealists pioneered it as a method for accessing the unconscious mind’s creative potential. The technique fascinates me because of its capacity for surprise — the hand produces forms the conscious mind didn’t choose, and the artist becomes the first viewer of their own work. I created over twenty drawings consecutively, in concentrated sessions, maintaining mental emptiness throughout. I titled the series only after completing and analysing all the pieces. The name had to come from what the drawings revealed, not from any prior intention. What they revealed were forms resembling bacteria, cells, and organisms. Structures that looked grown rather than designed.

Why biological?

I don’t know. What drove my mind to generate these particular shapes? Why did the unknown variable resolve into something so distinctly organic?

I’ve left this question open, though it prompted reflection about my circumstances and mental state during that period. The project proved both fascinating and therapeutic — a demonstration of art’s dual capacity for aesthetic expression and psychological excavation.

The connection isn’t accidental. Biomorphic abstraction — the artistic tendency toward organic, rounded, vaguely biological forms — emerged in the early twentieth century through artists like Jean Arp and Yves Tanguy. Studies of this tradition note that such forms often appear spontaneously when conscious control is released. There seems to be an innate human tendency to perceive and generate organic patterns. When the rational mind steps aside, something cellular surfaces.

Form and composition

I expected abstraction. I didn’t expect such uniformity. Despite their differences, all seventeen drawings share strikingly similar compositions: closed forms, centrally placed, with interconnected internal structures. This consistency emerged without planning. The concentrated work style — producing the entire series consecutively — may have reinforced it. Or perhaps the unconscious mind, given free rein, reveals its own persistent patterns. Art historians call this the “unconscious signature.” Individually, the drawings have a modest impact. Viewed together, the effect intensifies considerably. It functions as a series — repetition and variation, creating meaning that no single piece carries alone. This mirrors the way natural forms gain power through multiplication: cells, colonies, ecosystems. One organism is a specimen. Many become a system.

Continuation

I plan to create further series using the same methodology. The conversation with the unconscious isn’t finished. For anyone curious: try it. Bypass intention. Let the hand move. See what surfaces. The results tend to be more revealing than comfortable — which is precisely the point.