Sketching Cats

Field notes

The pencil hovers. The cat sits perfectly still, tail wrapped around paws, eyes half-closed. Then — movement. A twitch of whiskers, a turn of the head toward something invisible, and the pose is gone. This is the problem with sketching cats. They won’t hold still. They won’t cooperate. They exist in a state of perpetual almost — almost relaxed, almost asleep, almost still enough to draw. And yet artists keep trying. From Egyptian tomb paintings to Instagram accounts with millions of followers. Cats prowl through art history, resistant to capture, and endlessly drawn.

Paradox of form

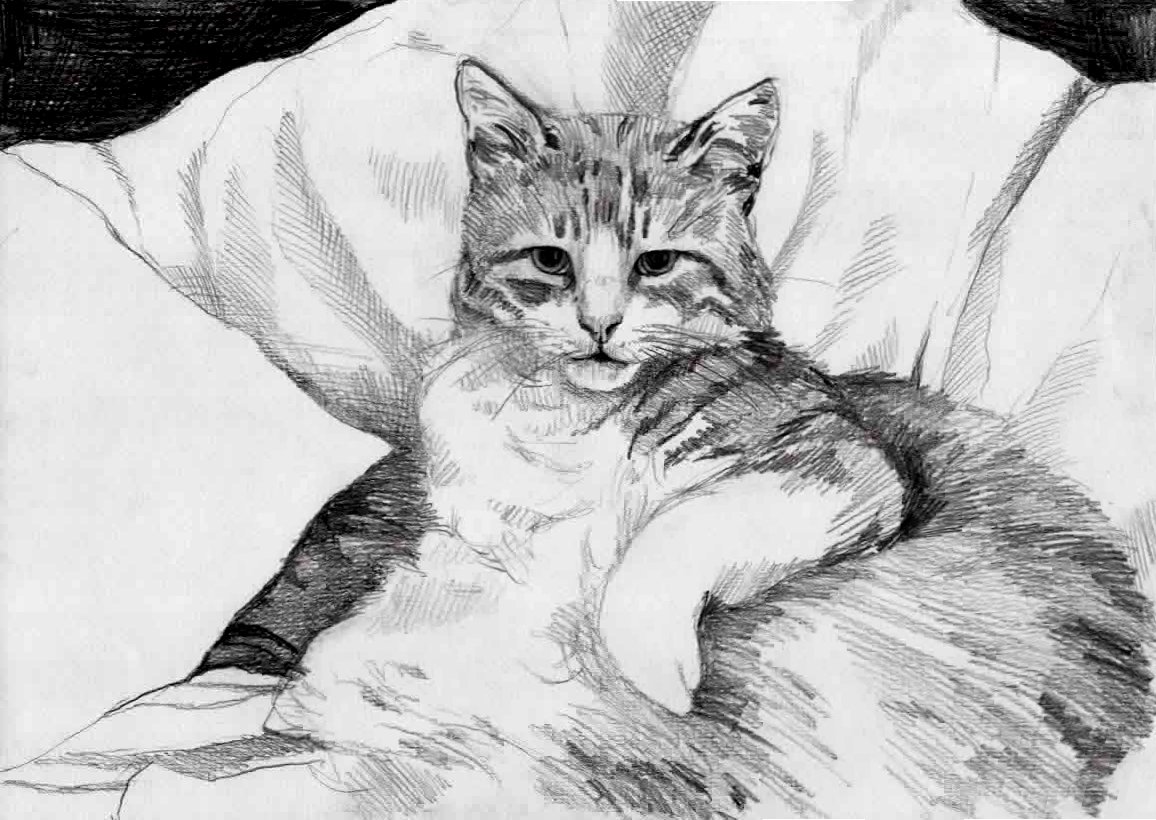

A cat is a study in contradiction. The same paw that kneads softly against your lap conceals retractable claws. The fur that invites touch can bristle into threat. The eyes that gaze with apparent contentment can dilate into black pools of predatory focus. These shifts happen in seconds.

The physical form changes with mood. A relaxed cat is liquid — it flows into containers, drapes over edges, pools in sunlight. An alarmed cat is architecture — arched back, rigid legs, puffed tail doubling its volume. Same animal. Same bones and muscles. Completely different shape.

The tail alone is a whole vocabulary. Upright with a curved tip: contentment. Low and twitching: irritation. Puffed and vertical: fear. The artist who learns to read these signals understands not just where to place the tail, but what kind of line the whole drawing needs.

Speed over precision

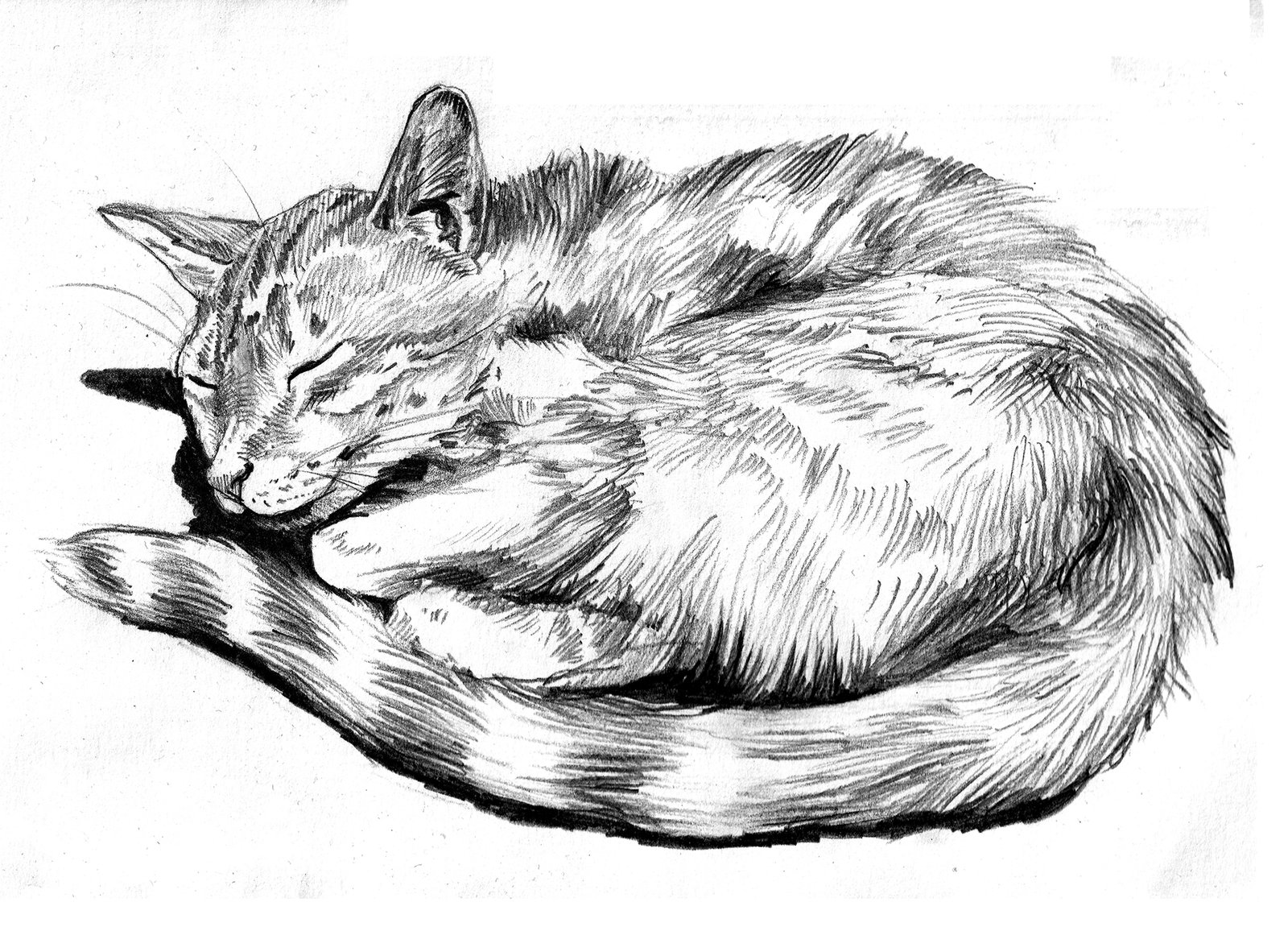

Cats don’t wait. A ten-second gesture drawing often captures more truth than a laboured study. The quick sketch catches what matters: the line of action running through even a resting cat, the coiled potential in a seemingly relaxed pose, the spring-loaded quality that distinguishes feline stillness from actual relaxation.

When cats move, they flow. Unlike dogs, who travel in straight lines with a visible purpose, cats navigate in curves and spirals. They pour themselves down from heights. They materialise in unexpected places. Capturing this requires what might be called gestural empathy — feeling the movement in your own body while drawing it.

Work fast. Accept incompleteness. The blur of a quick sketch often conveys more motion than a frozen, detailed rendering ever could.

Problem of fur

Cat fur defeats many artists. It isn’t uniform — short velvet on the face, longer tufts at the neck, sleek along the spine, downy on the belly. Light plays across these surfaces differently, creating patterns that shift as the cat breathes.

But fur isn’t merely covering. It’s an expression. A calm cat’s fur lies flat. Excitement makes it ripple. Fear makes it stand on end. Cold makes it puff. These changes transform the entire silhouette.

The solution is restraint. Heavy lines kill the softness. Overworking eliminates it. The lightest marks — suggesting rather than defining, leaving paper untouched — convey what dense rendering destroys.

Particular cat

Every cat is unmistakably a cat. Every cat is also unique.

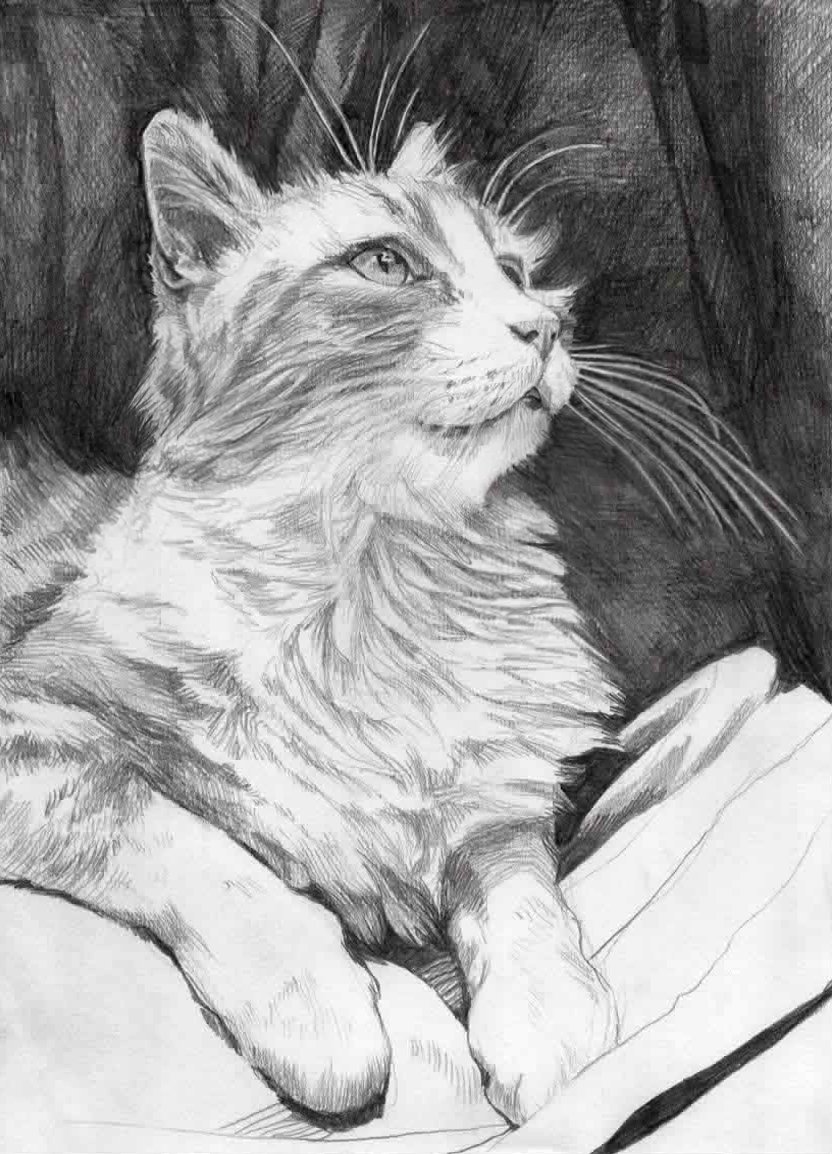

The challenge: capture both the universal feline and the individual animal. This demands observation of the particular. One cat tucks its paws a certain way. Another holds its whiskers at an unusual angle. Some have asymmetrical markings that lend their faces distinct expressions. These details transform a generic cat drawing into a portrait.

Artists who live with cats have an advantage. Daily observation reveals what casual encounters miss. The cat who always sleeps in a specific twisted position. The one who sits with one paw slightly extended. The habitual head-tilter. These poses become signatures.

Any cat is a worthy subject. The scruffy stray on a wall offers as much as the pedigreed Persian. Cats who’ve lived harder lives often show more character — the notched ear from old fights, the cautious posture of hard-won wisdom. Their bodies tell stories.

The unknowable

The greatest challenge in sketching cats is conveying what cannot be conveyed: the sense of a consciousness operating by different rules.

This shows most clearly in the eyes. Cat eyes reflect light strangely, seeming to glow from within. They appear knowing one moment, vacant the next. What do you draw — what you see, or what you imagine lies behind it?

The answer may be to leave something unresolved. The best cat sketches don’t explain. They preserve the encounter with something essentially other. Quick sketches succeed where laboured drawings fail precisely because they don’t attempt to pin down what cannot be pinned.

Play and mischief

Cats at play abandon all dignity. The elegant creature becomes a whirlwind — toys attacked with mock ferocity, invisible enemies stalked and pounced upon, ordinary objects fascinating for no apparent reason.

Drawing this requires abandoning precision. The line must become playful. Multiple quick strokes suggesting several positions at once convey the cat that seems to occupy different places simultaneously.

Then there’s deliberate mischief. The cat who knocks objects off tables whilst maintaining eye contact. The one who demands attention at the worst possible moment. This isn’t reactive behaviour. It’s creative. Almost artistic.

Softness

For all their wildness, cats possess extraordinary softness. Not just physical — though cat fur is legendarily soft — but something harder to name. A purring cat creates a field of contentment around itself. The weight of a cat in your lap differs from its ordinary weight. It’s a presence and absence at once.

To draw this requires slowing down. Entering something like the cat’s own sense of time, where urgency dissolves and the moment expands. You cannot render softness whilst rushed. The drawing knows.

Honesty of incompleteness

No single drawing captures all of what a cat is. The passive and active, soft and fierce, domestic and wild — these coexist in every individual, and no sketch holds all of them.

This isn’t failure. It’s recognition.

Cats remain compelling subjects because they cannot be fully captured. They slip between categories. They embody contradictions. The attempt to draw them, rather than any finished result, is where the work lives.

The pencil lifts. The cat, which had been posing perfectly, chooses this moment to stretch and walk away toward something of urgent feline importance. The sketch remains — incomplete, but true to its moment.

This is what sketching cats teaches: patience, acceptance of imperfection, and the value of the fleeting. Each drawing is a record of an encounter with a creature who shares our space whilst inhabiting a parallel world. Not definitive. Honest. That’s enough.